Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973) has entered literary history as a leading twentieth-century author. In Germany and Austria, her status as a feminist writer matches that of Simone de Beauvoir in France, Virginia Woolf in Britain, and Sylvia Plath in the US. Bachmann did a PhD in philosophy, then made her name first as a poet before producing two volumes of short fiction and, finally, the classic modernist novel Malina (1971), the only completed part of a trilogy she entitled Todesarten [“modes of death”]. In the twenty-first century, her correspondence with the poet Paul Celan was a significant publishing event, even becoming the basis for a film directed by the celebrated documentarist Ruth Beckermann[1]. This followed a volume of letters with the composer Hans Werner Henze, which is relevant to Bachmann’s reports from Rome for Radio Bremen to the extent that Henze too lived in Italy (as a gay man and a communist Henze wanted to get out of West Germany). He recommended that Bachmann move there too. Their correspondence is sadly uneven, as, like so many male correspondents through literary history, Henze did not keep what his female correspondent wrote to him[2]. It is indicative of the contradiction between Bachmann’s practice as a writer of literary letters and her conception of the inferior status of her radio journalism that they never discussed the reports for Radio Bremen which she filed under the name, Ruth Keller.

The young Bachmann was an experienced writer for radio; indeed, it was the only paid job she ever really had. From the late 1940s she worked for the Vienna-based American radio station Rot-Weiss-Rot as an editor. She also regularly wrote episodes for the drama series “Radio Familie Floriana” and was acclaimed for her fluency and humour, submitting her scripts punctually week by week. And of course, she is the author of radio plays or Hörspiele, which have always counted as an integral part of her oeuvre, though their place in it is arguably less prestigious than that of her other pieces. Radio was the key employer for West German and Austrian writers in the first post-war decade. “We all lived from the radio”, said Hans Werner Richter, the convenor of the Gruppe 47 which championed Bachmann in the early 1950s[3]. The regional public service broadcasters in the new Federal Republic, set up by the Allies after 1945 and modelled on the BBC, were well funded, depending then as now on compulsory subscriptions form every household, so-called Rundfunkgebühren. They were independent of the government and obliged to aim for “balance” with an educative or rather “re-educative” mission. This seems relevant to an evaluation of Bachmann’s reports on Italian politics for Radio Bremen in 1954-55 which are the subject of this paper: Bachmann or her editors (or both in combination) uphold a certain idea of western parliamentary democracy at key moments, railing against both the far left and the far right but identifying the greater threat to the newly re-established democratic order to be from “leftwing extremists”. In other words, Bachmann’s Römische Reportagen are dispatches from the front in the Cold War.

When Bachmann moved to Rome in the summer of 1954 after spending time with Henze in Istria (until 1918 part of Austria-Hungary), then moving on to Naples, she was twenty-eight years old, and had just published her first volume of poetry Die gestundete Zeit [Deferred Time). Bachmann was fluent in Italian with a deep knowledge of the country, albeit that she had visited for the first time just two years previously. She needed money, having just gone freelance, and it is for that reason that for a period of just under a year, between 15 July 1954 and 9 June 1955, under the pseudonym Ruth Keller, Bachmann wrote a regular series of reports for the regional broadcaster Radio Bremen. She would discuss her topic with an editor and the following day dictate her copy down the phone. Her reports were then read out by a third voice in a feature entitled Foreign Correspondents. Bachmann’s identity was thus doubly obscured, behind an assumed name and another’s voice. One problem of researching “la voix sur les ondes” is that the broadcasts themselves have been lost. Only the transcripts of the telephone conversations have survived in Radio Bremen’s archives, where they were located in the mid-1990s, resulting in the annotated paperback Römische Reportagen: Eine Wiederentdeckung [Reports from Rome: A Rediscovery] in 1998[4]. To date, they have not received critical attention from Bachmann scholars, which is surprising given that they are an industrious group on the whole. While a chapter written in 2011 about Bachmann’s work in Italy acknowledges the Reports’ existence, they are dealt with in just one sentence[5]. In her generally masterly biography, Andrea Stoll sums them up in four sentences, describing their contents as follows: “Bachmann schreibt über den neuen Fiat Populare S 600 genauso wie über die chaotischen Verkehrsverhältnisse, decadent-bizarre Kriminalfälle in der römischen High Society, Parteiengezänk, Naturkatastrophen und die Mafia” [Bachmann writes about the new Fiat Populare S 600 as well as about the chaotic conditions on the roads, bizarrely decadent criminal cases among Rome’s High Society, arguments between the political parties, natural catastrophes and the mafia[6].]

It is the premise of this paper that “the bizarrely decadent criminal cases among Rome’s High Society”, which later impacted films directed by Fererico Fellini (La Dolce Vita, 1960) and Jess Franco (Venus in Furs, 1969), got to the heart of injustice between the sexes in the 1950s. Bachmann did not deal comprehensively with sexual politics and gender identity until her acclaimed novel Malina, which was quickly acknowledged not only as a masterpiece of late German modernism but also a key feminist text.

As part of Bachmann’s Italian oeuvre, these reports could be placed next to the contemporaneous essay “Was ich in Rom sah” [What I saw in Rome], published in the trend-setting literary journal Akzente in February 1955, or the translations of the poet Ungaretti, which were published in a bilingual volume by Suhrkamp in 1961[7]. However, that is not what has happened. Broadcast journalism is considered functional rather than literary. In 1978, the editors of Bachmann’s collected works had no knowledge of the Römische Reportagen because they could not be found amongst her papers. In contrast, the smaller number of articles which were also signed Ruth Keller published in the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung over an overlapping period were deliberately omitted[8]. Newspaper articles turn up amongst a writer’s papers, but radio broadcasts do not. Bachmann’s use of a pseudonym may indicate that she was distancing herself from what she regarded as a less important genre of writing which may have been subjected to intrusive editorial interventions. Thus, it was her view too that the reports do not belong to her oeuvre. On the other hand, the pseudonym gave her some creative freedom. There can be a variety of reasons for writers to publish under different names. Hans Magnus Enzensberger, a contemporary who also worked as a radio editor and who exchanged letters with Bachmann, wrote under several aliases throughout his career.

Bachmann alias Keller’s style and technique nevertheless merit further study. The reports contain a large amount of information and some statistics. According to her biographer, Bachmann simply absorbed what the Italian press was reporting and summarised it[9]. In other words, she did not do “hard news” or find out for herself what was going on by attending press conferences, for example. There are no vox populi in the form of journalist interviews or quotations from the man or woman “on the street”, though (notably using the “neutral” male form) she often invokes “der kleine Mann” (the little man), “der Durchschnittsitaliener” (the average Italian [man]) or “der Mann auf der Strasse” (the man on the street) to ask what Italians may think of what is going on. Instead of on-the-ground reporting, what her listeners get are verbatim quotations from print news outlets or paraphrases of what has been published in the Italian newspapers. She refers to “the press loyal to the government” (20) and the “front-covers of the news weeklies”, as well as the following titles: Tempo, Epoca, Messagero, said to be supportive of the government coalition led by Prime Minister Mario Scelba, La Stampa, Il Corriere della Sera, the Communist daily Unità, and the conservative Giornale d’Italia. Bachmann is thus commenting on journalism which she treats as a pre- or proto-literary form rather than a reflection of reality.

Bachmann alias Keller pursued a consistent policy with respect to content selection. She focussed mainly on political topics of relevance beyond Italy. These included the stability of the government or indeed the state itself in the shape of the new republic as well as international relations and developments which were shaping the post-war order. What happened in Italy was of interest to West Germans because the two countries shared a post-Fascist geopolitical space in the Cold War, with a potentially fragile consensus that republicanism was the most appropriate form of government. Italy had voted with a narrow majority in a referendum for a republic over a monarchy, as Keller reports. The Communist Party, the second most powerful in Europe, as stated in her second dispatch, wanted to overthrow the state as constituted at the time. There were many parallels with West Germany (where the Kommunistische Partei was banned in 1956) and in Bachmann’s native Austria, which remained under Allied occupation until 1955. The failure of a recent initiative to constitute a European Defence Community; Italian views of the Paris Treaties, which saw the Federal Republic join NATO; and the Italian role in the beginnings of the inter-state consortium that would become the EU, were all European rather than purely Italian concerns. The same applies to a diplomatic visit by the French Prime Minister Pierre Mendès France and the disapproval expressed by the US Ambassador Clare Boothe Luce over the election of a new Italian President. That “building Europe”, whatever that might mean in practice, must be a good thing emerges as an unstated assumption in Bachmann’s Italian journalism: Bachmann and her employers at Radio Bremen were in favour of intra-European co-operation. The origins of what is now called the European Union date back to 1956, the year following the last of the Italian reports.

Bachmann alias Keller’s perspective on her subject shows a nuanced understanding of her role. She is occasionally ironic but never sarcastic. She usually avoids writing about “the Italians” in the third person, that is, as a group who are distinct from both her and her German listeners, though she does do so occasionally. However, looking back on her attitudes to the country she made her home, she finds that it would be equally redundant to write from an Italian point of view. Her solution was to try to write with Italians from their midst rather than about them. In an interview conducted in Rome shortly before her death in 1973 at the age of 47, Bachmann spoke about her relationship with Italy: “Die Probleme Italiens glaube ich zu kennen und es nicht eine Identifikation, sondern es ist ein Mitdenken und ein Mitgehen mit diesen Menschen” [I believe that I know Italy’s problems and it is not that I identify with the Italians, rather it is a case of my thinking with them and walking the road with them][10]. Italy could only ever be half-abroad for someone brought up in the Austrian province of Carinthia:

My decision to go to Italy was not a decision such as that taken by others, such as the British, the Germans or the Austrians, to get on the train and head south; you see, I come from the Italian border, the Italian border was a few kilometers from where I grew up. Italian was my second language; although of course it only really became my second language in the course of the years[11].

However, these theoretical strictures apply to Ingeborg Bachmann the literary writer. Ruth Keller has greater freedom to follow the conventions of her rather different métier.

In these reports, Bachmann never uses “ich” (I), and never reveals personal involvement, her positionality or opinion. Nonetheless, from the outset, she establishes a distinctive voice and clearly wants to grab and keep her listeners’ attention. The metonymic use of Rome and Italy becomes something of a trope. “Ganz Italien ist aufgeregt” [All Italy is agitated], she begins on 27 April 1955. The opening often establishes an immediacy, with a topic sentence often beginning a story in medias res. This is a technique designed for radio. She starts her very first report, which is about a deadly parasite attacking farm crops, with a metaphor designed to wrong-foot the listener: “Das Gebiet um Modena und die ‘rote’ Emilia befinden sich im Alarmzustand” [The area around Modena and ‘red’ Emilia find themselves in a state of alarm]. Emilia Romagna is a bastion of the Partito Comunista Italiana (PCI) and known as “red” for that reason. The cause of the state of alarm this time, however, is an agricultural pest. The danger it poses sounds alarming indeed, but there is no further mention of it. The date is 15 July, the beginning of the “Sommerloch” or “silly season” of slow news, to which Bachmann alludes nearly four weeks later in her next report from 10 August, which is promptly followed by another on 11 August – as if she had saved up too much material for one day, to the delight of the August editor at Radio Bremen who needed material.

The first sentence of this second report is equally witty and makes good the promise of the first: “Wenn man aus Italien das Wort ‘Streik’ hört, ist man geneigt zu sagen: ‘Im Süden nichts Neues’” [If you hear the word ‘strike’ in connection with Italy, you are inclined to say: All Quiet on the Southern Front]. Here Bachmann positions the article and the reader on the outside of the story: Italians are fulfilling a national stereotype by having so many strikes. What is different is that these strikes now form part of a “kalter Aufstand” [cold uprising] to bring about the third revolution after the failure of the revolutions following the two world wars, in 1919-20 and 1944-46. The workers, or at least their leaders, are plotting the overthrow of the state by withdrawing their labour en masse. As they appear to have been conducting these plots in public, there may have been a certain performativity to their rhetoric, but, according to Bachmann, a similar strategy was pursued in Prague in 1948 in the run-up to the Soviet-backed coup. Bachmann notes ominously that the current Soviet ambassador to Rome was ambassador to Czechoslovakia six years ago. On 11 August 1954, she begins: “Mit Spannung erwartet Rom die offizielle Veröffentlichung der neuen britisch-amerikanischen Vorschläge zur Lösung des Triestproblems” [Rome is awaiting with anxiety the official publication of the new Anglo-American proposals to solve the Trieste problem]. The status of the border city of Trieste, part of Austria-Hungary until the end of World War One, had yet to be decided. The Trieste talks, which are ultimately resolved amicably to each side’s satisfaction, form more than general backdrop. They provide the substance for two reports and are a piece in the mosaic of post-war reconstruction and reconciliation.

The single greatest news item over her fifteen months as the Roman eyes and ears of Radio Bremen is the Montesi Affair, which had in fact begun some fifteen months before Bachmann arrived in Rome and would continue for more than two years after she filed her last report from the city. The affair also threatened to destabilise the young Italian republic. It showed how senior male figures connected to the government and protected by the police and the judiciary lived for pleasure at the expense of the rest of the population, which was in this case was represented by a young working-class woman named Wilma Montesi whose half-naked corpse was washed up on a beach near Rome on 10 April 1953. At first it was said that Montesi must have slipped into the sea from sitting on a rock to wash her feet. According to this theory, the current then carried her body two kilometres in 24 hours to the location where it was found. An inquiry led by the investigative journalist Silvano Muto for the magazine Attualità discredited this account. There was no evidence that Montesi had been sexually assaulted, however, and no alcohol or other substances were found in her blood stream, although sand found inside her vagina could only have been the result of a struggle.

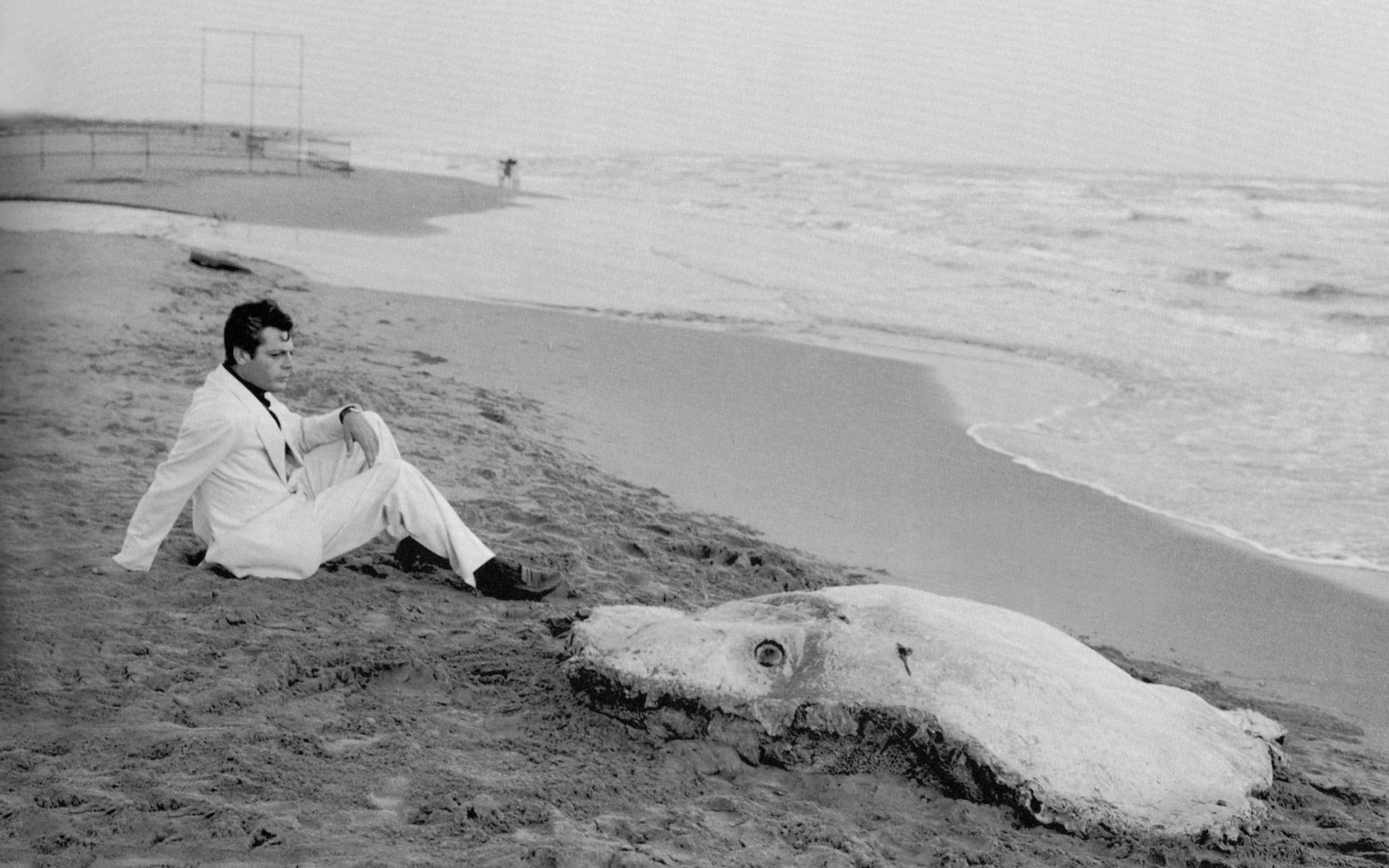

Bachmann writes about the affair through the autumn of 1954 and again in the spring of 1955. It turns out to be pivotal in respect of her coverage of the threat posed to the state by the PCI. The Montesi Affair and its ramifications in the worlds of politics, high society and showbusiness have been the subject of several books and depicted in cinema[12]. At the end of Fellini’s epoch-defining film La dolce vita (1960), privileged partygoers emerge at dawn to find a monstrous one-eyed jellyfish lying on the sand. In Franco’s Venus in Furs (1969), the victim, Wanda Reed, returns from the dead to avenge her murder which was witnessed by the film’s central character and narrator, who plays trumpet in a jazz band. One of Wanda’s murderers is Ahmed Kortobawi played by Klaus Kinski. At the end of the film, the trumpet player confesses that he not only witnessed the murder but in fact took part in it, as he looks at his own body now washing up on the beach.

Bachmann alias Keller takes a different line to the two films, which both impute guilt to self-indulgent elites. At first, however, for her too, the affair is emblematic of the moral corruption at the heart of the Italian state. Once Muto’s defence lawyer Giuseppe Sotgiu, a leading member of the PCI, is revealed have unusual sexual tastes himself, the Left-led campaign against the government apparently backfires. Radio Bremen listeners are spared the interesting details, but readers of the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung learn that Sotgiu and his wife, an artist named Liliana Grimaldi, visited brothels together (Keller does not say so, but it was to give Sotgiu the opportunity to watch Grimaldi having sex with a young man[13]). Keller also discredits Silvano Muto whom she claims was interested in increasing the sales of his magazine. By February 1955, Bachmann claims that he has decided to give up journalism for the sake of an academic career (p.47). Muto, however, maintained his innocence of “spreading false and tendentious news to disturb public order” and the case against him soon collapsed[14].

Bachmann alias Keller is interested in news as spectacle and in how the story is reported, disseminated, and controlled. She accords the print media great power. After the arrest on charges of negligent homicide of Piero Piccioni, a jazz musician like the hero of Franco’s film, whose father happened to be the Italian Foreign Minister, newspaper sellers were under instructions not to shout out the headlines “um keine unnötige Aufregung in der Bevölkerung auszulösen” (p.18, in order not to incite unnecessary agitation in the population). Keller begins on 9 September 1954: “Rom hat heute morgen nach einem ereignissarmen Sommer einen ‘Colpo di scena‘ erlebt, einen Theatercoup in Form einer ebenso unerwarteten wie dramatischen Wendung um vielbesprochenen Fall Montesi” [After a summer in which not much happened Rome has this morning witnessed a colpo di scena or coup de theatre in the form or twist in the much discussed Montesi case which is as unexpected as it is dramatic]. The colpo di scena is that three individuals had their passports confiscated, pending further investigations into their involvement. In addition to the trumpet-playing son of the Foreign Minister, there are the Marquis Ugo Montagna, owner of a hunting lodge at Capocotta near Rome, and the Rome police chief. A third young man, the German Prince Moritz von Hessen, had an alibi that he was in the company of his girlfriend at the time that Montesi died.

On 22 September 1954, when a new twist to the tale is revealed, Bachmann cites the aria ‘Nessun dorma’ from Puccini’s Turandot: “Rom und die italienische Regierung haben eine schlaflose Nacht hinter sich.” [Rome and the Italian government have a sleepless night behind them]. She is evidently enjoying the way that this story keeps unfurling and ends by comparing the real-life affair with the plot of detective novels written by Agatha Christie and Edgar Wallace. Bachmann is interested that six months later the participants are writing their memoirs, thus turning the affair into literature. One of the women involved is said to be receiving offers from film companies, another modelling her account on the novel of the season, Bonjour Tristesse by Francoise Sagan. Bachmann’s final report on Montesi indeed reads like a pitch for a film with the girlfriend of one of the men Adrianna Bisaccia in the role played by Nico in La Dolce Vita: “Existentialistin, Prototyp des abenteurenden Mädchens aus der Provinz, deren Stellung in der Montesi-Affäre noch völlig ungeklärt ist” (p.47, A female existentialist, the prototype of the provincial adventuress, whose involvement in the Montesi Affair remains completely unclear).

According to Bachmann, the state played its hand well with respect to Montesi: investigations and court proceedings took place in public. Investigators could not lay their hands on a smoking gun and voters could see that there was no cover-up. The accused conducted themselves with grace in custody and waited for public opinion to swing behind them. Writing as Ruth Keller, Ingeborg Bachmann thus aligns herself with the authorities, while Leftist attacks on elites were designed to weaken trust in national institutions.

What can we read into Bachmann’s conservative and less-than-curious approach to this scandal centring on a young woman who died in suspicious circumstances, which contrasts sharply to the approaches of the filmmakers, Fellini and Franco, and to cultural historians? Perhaps the clue is that it was not Ingeborg Bachmann writing at all, but Ruth Keller. Read in the era of gender-inclusive language, Keller’s use of the male forms shows how in the 1950s a woman who wrote was obliged to disguise her own gender identity and refer to “the common man”, “the man on the street”, or “the average Italian [man]” (Durchschnittsitaliener). Did Bachmann also hide her own feminine sensibility when it came to her reporting of the death of a woman just six years her junior? That could be the principal difference between literary writing, which rightly belongs to a writer’s oeuvre, and functional reporting which is ephemeral, dictated down the phone to be read out by an anonymous voice under a pseudonym. In her most celebrated “Erzählung” [story] Drei Wege zum See [Three Paths to the Lake], the central female character is a photojournalist who, aged 50, returns not from Rome but from London to her home city of Klagenfurt, where Bachmann herself was born and grew up[15]. She reflects on her career and how she learnt from male figures how to thrive in a world governed by men. She reports on episodes in the global Cold War, much as Bachmann alias Keller did by reading the Italian press, the difference being that she is there in person with her camera and not reliant on newspapers[16]. Giving the central character in this auto-fictional long short story the profession of foreign correspondent, albeit one who gives up the pen for the camera, shows the importance that Bachmann attached to the role. The nameless female narrator of Malina known only as “ich” also once worked in journalism. This remarkable novel in which Bachmann experiments with narrative form to explore the narrator’s conflicted identity and ultimate inability to lead both a successful independent life and be a woman at the same time may contain traces of the Montesi Affair. On the last page of the novel “ich” disappears into a crack in the wall after surrendering her identity to her male alter ego after the whom the novel is called. Except that “ich” did not surrender her female identity voluntarily as the last line of the novel makes clear: “Es war Mord” [it was murder]. The whole novel is thus written from the perspective of a woman who has been murdered. The second section “Der dritte Mann” consists of nightmarish accounts of female suffering which include drowning. The “Friedhof der ermordeten Töchter” [cemetery of murdered daughters] is next to water on the banks of a lake[17]. In the third and final section, “Von letzten Dingen” [Of last things], “ich” fears that she will become the victim of a sex murderer:

The newspapers often contain these horrible reports. In Pötzleinsdorf, in the Prater water meadows, in the Vienna Woods, on every ring road a woman has been murdered, strangled – it nearly happened to me too, but not on the ring road -, throttled by a brutal individual, and I always think to myself: that could be you, that will be you[18].

“Ich” does not reveal her name. Malina as her imagined male alter ego succeeds in his career and dealings with the world by suppressing those memories and emotions which are attached to “ich”, in other words his. Bachmann alias Keller does not even say “ich” in her reports from Rome but instead presents herself as an Everyman who takes faits divers of the suspicious death of an innocent young woman in his stride. The death returns to haunt her later fiction.

Marcello Mastroianni as the high society reporter Marcello and the monstrous jellyfish at the end of La Dolce Vita (1960, dir. Ferderico Fellini).

Maria Röhm as Wanda Reed, “the body on the beach” in Venus in Furs (1969, dir. Jess Franco).

Notes

[1] Ingeborg Bachmann, Paul Celan, Herzzeit. Briefwechsel [Heart Time. Correspondence], edited by Bertrand Badiou, Hans Höller, Andrea Stoll and Barbara Wiedemann, Frankfurt, Suhrkamp, 2008. See Die Geträumten [The Dreamed Ones] (2016, dir. Ruth Beckermann).

[2] Ingeborg Bachmann, Hans Werner Henze, Briefe einer Freundschaft [Letters in a Friendship], edited by Hans Höller, Munich, Piper, 2005.

[3] Quoted by Andrea Stoll, Ingeborg Bachmann. Der dunkle Glanz der Freiheit [The Dark Glow of Freedom], Munich, btb, 2013, p.122.

[4] Ingeborg Bachmann, Römische Reportagen. Eine Wiederentdeckung. [Reports from Rome: A Rediscovery] Munich, Piper, 1998.

[5] Auturo Larcati, ‘Diva-Kind und Intellektuelle. Ingeborg Bachmann in Italien‘, in Wilhelm Hemecker and Manfred Mittermayer (eds.), Mythos Bachmann. Zwischen Inszenierung und Selbstinszenierung [The Bachmann Myth: Presentation and Self-Presentation],Vienna, Zsolany, 2011, p.241-62.

[6] Andrea Stoll, op. cit., 2013, p.150

[7] Ingeborg Bachmann, “Was ich in Rom sah”, in Werke, 4 vols, edited by Christine Koschel, Inge von Weidenmann and Clemens Münster, Munich, Piper, 1978, vol. 1, p. 29-34.

[8] Vol. 4, p.406.

[9] Stoll, op. cit., p.150.

[10] Ingeborg Bachmann, Ein Tag wird kommen. Gespräche in Rom. Ein Porträt von Gerda Haller. Mit einem Nachwort von Hans Höller. [A Day Will Come. Interviews in Rome. A Profile by Gerda Haller. With an Afterword by Hans Höller] Salzburg/Vienna, Jung and Jung, 2004, p.45.

[11] “Der Entschluss für mich, nach Italien zu gehen, war nicht für mich ein Entschluss, wie es ihn für andere gibt oder etwa der Zug nach Süden der Engländer, der Deutschen, der Österreicher; denn ich komme schon von der italienischen Grenze, bin wenige Kilometer von der italienischen Grenze aufgewachsen. Italienisch war meine zweite Sprache; obwohl es natürlich erst im Verlauf der Jahre wirklich meine zweite Sprache geworden ist.”, ibid., p. 47 (traduction de Julian Preece).

[12] See Stephen Gundle, Death and the Dolce Vita: The Dark Side of Rome in the 1950s, London, Canongate, 2011 and Shawn Levy, Dolce Vita Confidential: Fellini, Loren, Pucci, Paparazzi, and the Swinging High Life of 1950s Rome, New York / London, Norton, 2016.

[13] See Gundle, op. cit., p.182 and Levy, op. cit., p. 100.

[14] Gundle, op. cit., p. 111-32.

[15] Ingeborg Bachmann, ‘Drei Wege zum See’, in Simultan [Simultaneous], Frankfurt, Suhrkamp, 1972, p. 130-233.

[16] On Bachmann and the Cold War, see Sara Lennox, “Gender, the Cold War, and Ingeborg Bachmann”, in Caitriona Leahy and Bernadette Cronin (eds.), To Ingeborg Bachmann: New Essays and Performances. Würzburg, Königshausen & Neumann, 2006, p. 223-38, esp. p. 227 where Lennox briefly discusses Römische Reportagen.

[17] Ingeborg Bachmann, Malina (1973), Frankfurt, Suhrkamp, 1980, p. 207.

[18] “In den Zeitungen stehen oft diese grässlichen Nachrichten. In Pötzleinsdorf, in den Praterauen, im Wienerwald, an jeder Peripherie ist eine Frau ermordet worden, stranguliert – mir ist das ja auch beinah geschehen, aber nicht an der Peripherie -, erdrosselt von einem brutalen Individuum, und ich denke mir dann immer: das könntest du sein, das wirst du sein. ”, Malina, op. cit., p. 292-93.

Auteur

Julian Preece est professeur d’allemand à l’Université de Swansea depuis 2007. Il est l’auteur de plusieurs livres sur la culture allemande et autrichienne du XXe siècle : The Life and Work of Günter Grass : Literature, History, Politics (2001/2004) ; The Rediscovered Writings of Veza Canetti : Out of the Shadows of a Husband (2007) et Baader-Meinhof and the Novel : Narratives of the Nation, Fantasies of the Revolution, 1970-2010 (2012). Katharina Blum dans la série British Film Institute Classics est paru en 2022.